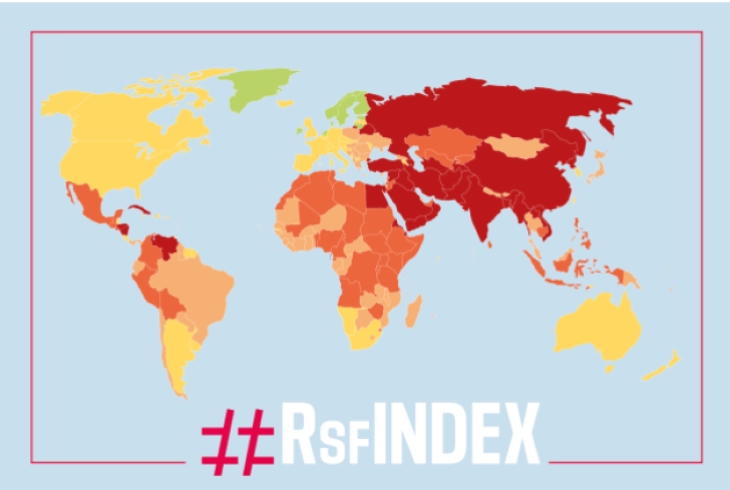

North Macedonia climbs 19 spots on 2023 World Press Freedom Index

- North Macedonia is ranked 38th out of 180 countries in the 2023 World Press Freedom Index, based on a report released by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), climbing 19 spots compared to its ranking in 2022.

- Post By Silvana Kocovska

- 09:37, 3 May, 2023

Skopje, 3 May 2023 (MIA) - North Macedonia is ranked 38th out of 180 countries in the 2023 World Press Freedom Index, based on a report released by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), climbing 19 spots compared to its ranking in 2022.

North Macedonia is also ranked the highest among the Western Balkan countries, ahead of Montenegro (39), Croatia (42), Kosovo (56), Bosnia and Herzegovina (64), Serbia (91) and Albania (96).

In its report on the country’s press environment, RSF said that although journalists do not work in a hostile environment, widespread misinformation and lack of professionalism contribute to society's declining trust in the media, which exposes independent outlets to threats and attacks. Furthermore, government officials tend to have poor and demeaning attitudes towards journalists.

Media landscape

Although television is the dominant source of information, online media play an important role. Yet, a distinction must be made between professional online newsrooms that employ professional journalists and publish original content, and individual portals that plagiarise and copy-paste such content. There is also a big gap between usage and trust: the most watched TV stations have a low reliability index.

Political context

The overall environment remains favourable to press freedom and allows for critical reporting, although transparency of institutions is rather poor. Due to strong political polarisation, the media can be subjected to pressure by the authorities, politicians and businessmen. The two largest parties (in power and in opposition) have created parallel media systems over which they exert their political and economic influence. The public broadcaster lacks editorial and financial independence.

Legal framework

While the constitution guarantees freedom of speech and bans censorship, the country is lagging behind in terms of harmonising media legislation with the standards of the European Union, which it intends to join. Judicial abuse of the Law on Civil Responsibility for Defamation incites self-censorship in the media. Lawsuits are used as a tool for intimidation and pressure on independent media. A bill to re-authorise the government to advertise in private media has raised concerns about possible influence peddling.

Economic context

Although certain types of media concentration are prohibited by law, the editorial staff of some of the major TV channels are exposed to economic pressures from their owners. State funding is limited and non-transparent, and independent media rely heavily on donors. Project-based foreign grants contribute to mere survival, but not to further development. There is influence peddling between marketing agencies and certain media outlets.

Sociocultural context

Although there are no clear constraints in the social and cultural environment that affect free journalism, social networks and the digital sphere generally favour the spread of disinformation and cyberthreats. Combined with low professional standards, they contribute to the decline of public trust in the media and pave the way for attacks on journalists based on gender, ethnic or religious criteria.

Safety

Journalists are regularly the targets of verbal attacks. Under the pretext of protecting state secrets and personal data, they may be exposed to legal pressure and abusive prosecution (gag proceedings or SLAPPs). However, the courts tend to uphold freedom of the press and protect journalists. In the capital city, a special prosecutor was appointed to handle cases of attacks against journalists, and the opening of similar offices across the country is under consideration.

Nordic countries lead World Press Freedom

Norway is ranked first for the seventh year running. But – unusually – a non-Nordic country is ranked second, namely Ireland (up 4 places at 2nd), ahead of Denmark (down 1 place at 3rd). The Netherlands (6th) has risen 22 places, recovering the position it had in 2021, before crime reporter Peter R. de Vries was murdered.The last three places are occupied solely by Asian countries: Vietnam (178th), which has almost completed its hunt of independent reporters and commentators; China (down 4 at 179th), the world’s biggest jailer of journalists and one of the biggest exporters of propaganda content; and, to no great surprise, North Korea (180th).

According to the 2023 World Press Freedom Index – which evaluates the environment for journalism in 180 countries and territories and is published on World Press Freedom Day (3 May) – the situation is “very serious” in 31 countries, “difficult” in 42, “problematic” in 55, and “good” or “satisfactory” in 52 countries. In other words, the environment for journalism is “bad” in seven out of ten countries, and satisfactory in only three out of ten.

The 2023 Index spotlights the rapid effects that the digital ecosystem’s fake content industry has had on press freedom. In 118 countries (two-thirds of the 180 countries evaluated by the Index), most of the Index questionnaire’s respondents reported that political actors in their countries were often or systematically involved in massive disinformation or propaganda campaigns. The difference is being blurred between true and false, real and artificial, facts and artifices, jeopardising the right to information. The unprecedented ability to tamper with content is being used to undermine those who embody quality journalism and weaken journalism itself. The remarkable development of artificial intelligence is wreaking further havoc on the media world.

Photo: Print screen/MIA archive