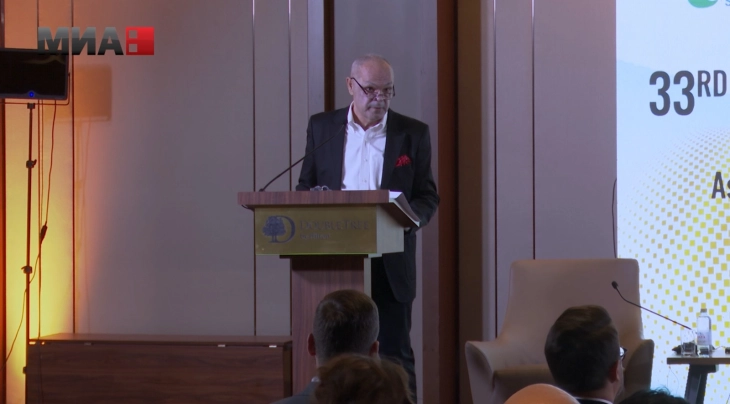

'Not enough for journalists to inform, they should investigate and uncover truth’: MIA Director Darko Janevski’s full speech at ABNA-SE Conference

- On August 2-5 Skopje hosted a conference of state news agencies from the Balkans, along with Italy’s ANSA, which was attended by the directors of the influential agencies. The event was addressed by Prime Minister Hristijan Mickoski, whose speech has already been published in full. Below is the full address delivered to the guests by the Director of MIA, Darko Janevski.

Skopje, 5 August 2025 (MIA)

Dear colleagues, dear friends, dear guests, allow me to open this Conference with the following topic, a topic concerning the true mission of journalism, the mission for which it exists and endures.

A challenge and a task that have existed since the very beginning of our profession, for some, a beautiful calling, for others, a brutally difficult and demanding job, yet one that brings extraordinary satisfaction when a successful result is achieved. I would kindly ask you later to share your views on this issue, so that we may enrich this gathering with your reflections which, although it may sound immodest, will enrich our lives and life in our societies.

An old rule says that a journalist has completed their work when they have information from at least two sources, preferably more. I’ve worked in several media outlets that dealt with stories involving serious accusations against individuals, and that always required additional verification. Sometimes, two sources aren’t enough. You need three, four sources, you need experts, and ultimately, you need your own reasoning and knowledge. This demands a lot of effort, decades of education, like doctors who must continuously learn new methods and practices throughout their lives. It also means that a journalist must sometimes have at least basic knowledge in multiple fields – politics, law, history, economics… and so on.

In life, I’ve met many journalists who are content with being “antennas” – transmitters of statements or reporters from events. That’s devastating. It’s hard to grasp that a journalist has spent years getting educated, invested effort, time, and energy, only to settle for holding a microphone in front of the mouth of someone giving a statement. Yes, a journalist should report and convey information, but nowadays, the ordinary citizen often doesn’t need a journalist to get information.

This drastically changes the role of the journalist. They must increasingly focus on investigating, on uncovering facts, without neglecting their duty to inform. The way information is delivered is also evolving. It’s no longer enough to simply relay bare facts, what increasingly matters more is whether, in the way you inform, you manage to infuse a touch of artistry, charm, and intelligence. To many colleagues for whom I’ve been an editor, I used to gift a copy of the novel “The Black Obelisk” by the great Erich Maria Remarque, telling them they should read it several times, explore his other works, and only then consider themselves ready to craft sentences beyond what I called the “journalistic antenna” style. In other words, we must take a step further, give readers something more than a plain, dry sentence.

But let me return to the matter of truth and lies in journalism. What is truth?

For Aristotle, truth is that which corresponds to reality.

For Nietzsche, truth is often “a collection of illusions we have forgotten are illusions.”

For Hegel, whose definition I like the most, truth is not something static, not merely a “correct statement,” but something that evolves, just as reality itself evolves.

For Marx, truth is material – it arises from the relationships within a society, especially from its economic basis.

And finally, I’d like to quote one of today’s most renowned physicists, Brian Cox, who says that “in science, there are no universal truths, just views of the world that have yet to be shown to be false.”

Can we grasp all of this as a whole and apply it in our work?

One of our diplomats would say: I don’t know. That’s a million-dollar question. And more.

Especially considering that astrophysicists speak of parallel dimensions, which implies the possibility of parallel truths. Theologians speak of a truth that exists beyond this world. Neurosurgeons talk about consciousness that exists independently, beyond the brain and body, a consciousness that is its own kind of truth. How do we navigate and deal with all of this? There’s another million-dollar question.

Today is 2025, the 21st century. Humanity has long since strayed from moral values. The race for money, which often become the main motive in modern life, pushes people to forget the truth. What matters to them is the goal, what matters is Machiavelli, not any kind of moral principle.

All of this is reflected in journalism as well. Not just in journalists, but in everyone who is part of a society. Because it’s not only journalism that’s affected. Until 1996, our Code of Criminal Procedure included an article that obligated the court – regardless of the arguments presented by prosecution or the defense – to determine the truth, which might lie with neither side. Because, as a famous television series once said: people know how to lie.

Later, with amendments to the Code, that article disappeared. Today, not only here but in many countries around the world, the court chooses between the arguments of the prosecution and those of the defense. It selects between what one side offers and what the other side offers. You could bring a dead body into the courtroom, but if neither the prosecutors nor the defendants see it, then it doesn’t exist for the court either.

And what is truth? Perhaps it is what the judge decides, but often it lies some third place. Somewhere hidden. Far from all of us. Something we may not even recognize as a problem. We’ve grown used to living as the wind carries us. The issue is that this hidden truth, as a way of behaving and living, is what we’ll pass on to our children.

That’s why the task of modern journalism is not just to inform, but to uncover the truth. To expose lies and present all of that to the citizen. To raise their awareness and improve their life.

I know, every journalist works for a salary. But so does every doctor. And yet, their primary goal is, above all, to save human lives. When they see a patient, do they think about how much they’re being paid? Yes, there are times when things become overwhelming. A Spanish doctor, when the COVID epidemic began and was asked how we should deal with it, replied:

“Why are you asking me to save you? Ask Leo Messi. You pay him a billion dollars, and me 1,800 euros a month.”

But she said that and then went back to saving lives. Because at that moment, what mattered more to her was uncovering what lay behind the virus, how to confront it, how to defeat it, rather than how much money she would earn by the end of the month. Imagine a scientist who merely announces that a virus exists, that it kills people, and then claims that by informing the public, their job is done. No, that scientist’s true task is to uncover the truth – how to overcome the virus.

It’s the same with us. We may complain about our status, but then we simply need to return to our work and do it as best we can in the interest of thousands and hundreds of thousands of people we don’t see and don’t know, and to be proud of that work. And we will have truly done our job when we present the truth. The truth we’ve made the effort to uncover. Not the truth that’s handed to us.

Of course, we’re not experts in every field. We’re not scientists. But that doesn’t stop us from searching, investigating, and discovering – not just informing.

Otherwise, we become vulnerable to manipulation, and when we are manipulated, we in turn manipulate the public. Let me return to the previously mentioned COVID epidemic. Was the virus artificially created or natural? Have we done our job if we ask two sources, one claiming it was artificial, the other saying it was natural? What have we achieved? We’ve confused our reader. Nothing more. I know many will say, we’re not experts in that field. True, but as individuals, based on the wealth of information we have compared to the average citizen, we can form our own judgment.

After all, you can see how truth itself changes, in line with how reality changes. During Anthony Fauci’s time, the virus was natural, originating from bats. Now, in the Senate of the world’s most powerful country, there is open discussion suggesting the virus was artificial. And we still aren’t experts in that field, but does our role boil down to simply relaying Fauci’s statements as absolute truth, and do the opposite with those who speak now?

Or perhaps we need to commit a little more. To be braver. Yes, that carries the risk of making mistakes, but is there any profession without the risk of mistakes? In all the chaos, it’s fortunate that our mistakes are rarely fatal. When a doctor makes a mistake, when a pilot makes a mistake, it can cost many human lives. And they cannot undo their error. We, even if we make a mistake, can correct it. And I believe the benefit of our pursuit of truth will always outweigh the harm we might occasionally cause.

That doesn’t mean we should rush. It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t verify. It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t inform. But, as I said, times have changed. And with that, the role of the journalist is changing too. Their primary goal should be the truth. And reaching it is not always easy.

Dear friends, I know that what I’ve said is nothing new to you. I’m not Columbus, and I’m not discovering a new continent. You are all top professionals, whom young journalists, and even the more experienced ones, can only envy.

But I felt that in this era of overwhelming information and even more disinformation, this needs to be emphasized once again and shared together as a value. Because sometimes, a human life may depend on our truth. Just as a lie, based on disinformation, can endanger that life. And none of us wants that, and that is the greatness of our profession. Thank you for your attention.