Bulgarian intellectuals: Macedonian has all the features of a literary language

- Post By Magdalena Reed

- 13:18, 27 July, 2022

Sofia, 27 July 2022 (MIA) — Language is what countries — especially developing ones — identify with. And no one can deny them the right to such self-identification. Professors Anna-Maria Totomanova and Aleksander Kyosev on the language dispute with the Republic of North Macedonia.

Aleksandar Andreev speaks with Aleksandar Kyosev, professor of Cultural History of Modern Europe and member of the Bulgarian-Macedonian Friendship Club, and Anna-Maria Totomanova, a renowned Bulgarian linguist and professor at Sofia's St. Kliment Ohridski University.

Andreev: From a political point of view, the Bulgarian MFA declaration that it does not recognize the Macedonian language, in my opinion, is simply a clumsy attempt at appeasing voters, especially those of There is Such a People, the party that nominated Minister Genchovska. The document has no international legal significance, so let's ask another question: Does a language need any special permission to exist, let alone the permission of a neighboring country?

Kyosev: That is a rhetorical question. No, a language spoken by millions of people, which is used in various walks of life and has its own tradition – such a language doesn’t need any permissions. A different matter altogether is asking the complex questions about recognizing the language’s historical origin.

Totomanova: We are talking about literary language, and literary language — in addition to being a social and cultural phenomenon, which language is in general — is also a political phenomenon. Language, especially the language of a nation, is what states, especially developing states, self-identify with. And no one can deny the right to such self-identification.

So why all this tension over the Macedonian language? The public statement released by the Bulgarian members of the [Bulgarian-Macedonian Friendship] Club, represented by Prof. Kyosev, said the Bulgarian MFA’s position "serves the interests of people on both sides of the border who have used the dispute to earn dividends.” Who are these people, Prof. Kyosev?

Kyosev: There are two main groups. One group is people who believe in romantic origin stories – they explain everything through going back in time. They think that if something comes from something, it is the same. I can give you thousands of examples disproving this view. Let's say, in one family, the daughter’s last name is Petrova, but then she marries and takes the last name Dimitrova, then her daughter marries and takes the last name Yancheva, etc. There is a process of natural name change that does not deny origins, and there is no need for romantic origin stories to dictate what the political name of a language should be. The other group consists of people who intentionally want to destroy the friendship between North Macedonia and Bulgaria. They want to prevent the unity of the Balkans and, of course, interfere in Europe. Russian interests are behind them.

Totomanova: In my opinion, “The Great Macedonians” on both sides of the border are behind this. These ones believe the Macedonian language is Bulgarian, those ones believe it isn’t.

That is, the same name — "Great Macedonians" — applies to two opposites, right?

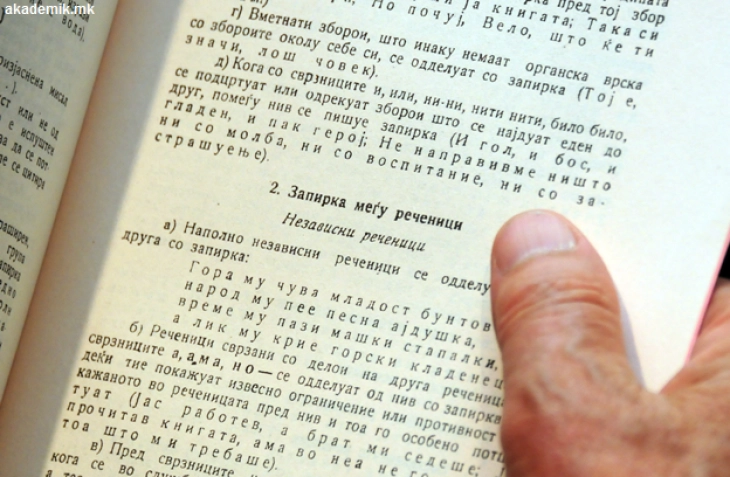

Totomanova: Exactly. Part of the problem, and this high degree of politicization of the language issue, stems from the fact there was not a single linguist in the so-called "Historian Commission” – made up of mostly historians, some archaeologists. They focused more on the roots. And the easiest way to take away people’s roots is to take away their language. On the other hand, we need to accept the fact that the Macedonian literary language, which is also the official language of the Republic of North Macedonia, has all the signs and features of a literary language. It is superdialectal, it is codified, it is used in all walks of life, such as politics and administration, and most importantly, it is the language of education. Almost four generations of Macedonians have been taught in the language, and not only Macedonians – also the Albanian minority and the country’s other ethnic communities. It is a different matter altogether that it was based on southwestern Bulgarian dialects.

And how does a dialect become a language?

Kyosev: There is a well-known funny remark by the great sociolinguist Max Reinhardt about this: "A language is a dialect with an army and a navy." That is, behind the language are state institutions, power, force, political will.

Totomanova: I agree. Language is a political phenomenon. It meets certain political needs. Another important thing: No literary language exists based on one dialect. The literary norm is a matter of convention and is usually a mix of different dialects. It is a matter of chance how this convention will be established.

Kyosev: It is by no means a matter of chance in Bulgaria. It is the result of the conflicts between different intellectual groups during the Revival and later. Various lobbies were fighting over whether the Bulgarian language should be codified on western or eastern dialects. And it was codified on the eastern dialects, but even then Petko Slaveykov and later Anton Strashimirov warned that in codifying it on the basis of eastern dialects, the western dialects would be excluded, which carried some risk for Bulgaria. The risk was great because the then region of Macedonia, where many people considered themselves Bulgarians, was outside these bounds and outside the cultural and educational policy of the Principality of Bulgaria. So these dialects had a completely different political fate.

Which is to say, today's Macedonian originated from shared dialects, but now it is a separate language?

Kyosev: Without a doubt, there are also people in North Macedonia who — going back to the origin story I was talking about — latch onto absolute fiction. They invent Macedonian language roots that seen through a historical, linguistic and political lens are somewhat ridiculous. There are people there who develop such phantasmagorias – just like there are people here who develop similar phantasmagorias.

Let's go back to the tension some Bulgarians feel regarding the language issue. Why do these people find the Macedonian language funny?

Totomanova: Because they perceive it as a Bulgarian dialect. Which is precisely why this viewpoint, which I think is supported by the Bulgarian Language Institute at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, is not methodologically sound. Literary language is not a dialectal phenomenon, it is superdialectal. Among other things, the same dialects that are the basis of the Macedonian language are also spoken in Pirin Macedonia. And that's why Macedonian seems funny to us.

Kyosev: Many years ago, a friend of mine told me: "I could never fall in love with a girl who speaks in a soft accent.” The language norm is a very strong norm; the Bulgarian language norm is very strong. And it requires sanctions. But the sanctions are mild: laughter, jest, irony. The best analogy is the separation of the Serbian and Croatian languages.

And now there are also Bosnian and Montenegrin.

Kyosev: They used to be called "Serbo-Croatian" and were divided for political reasons. This division was perceived as artificial for a long time – and it was indeed artificial to a certain extent. But gradually these languages began to develop independently, moving further apart from each other. I won't be surprised if in 50 years they need translation.

Totomanova: Every literary language has a certain degree of artificiality. It is not problematic when several literary norms are based on the same dialect material. It's been done since the dawn of time.

Kyosev: The adjective "artificial" is misleading. The holy brothers created an artificial language, yet it is a great creation. It was created by people. It did not sprout like tomatoes and cucumbers from the earth. That is, it is a social construction. And in this sense, it can be called "artificial" — in the “art” sense.

Andreev: Still, let's set this exciting academic territory aside and return to Bulgarian and Macedonian. Professor Totomanova said the Pirin dialect was very similar to the official Macedonian language in the Republic of North Macedonia. But official Macedonian is different, in my view, because it has absorbed many Serbian, English, and international words over the past decades. I have translated a lot from Macedonian and I can responsibly claim that translation between the two languages is definitely necessary — no matter that in Bulgaria you’ll hear the opposite. In my opinion, the issue of translation between the two languages has been made political for no reason.

Totomanova: It was made political by people who think the Macedonian language is a Bulgarian dialect. And the official Macedonian language is not completely comprehensible to Bulgarians, not even to those from Pirin Macedonia, because the language policy in Macedonia at the time when it was a Yugoslav republic had the exact opposite aim – and indeed went through a stage of Serbianization.

Kyosev: The need of translation is a practical matter that applies differently to different spheres of social communication. Obviously, in everyday conversations between Macedonians and Bulgarians, translation is almost unnecessary. However, there are different walks of public life where Macedonian and Bulgarian have developed in different directions, not only stylistically, but also terminologically.

In the end, what two scenarios do you see for the future, from a pessimistic and an optimistic point of view?

Totomanova: The optimistic one is to recognize the language, stop making such declarations and accept — together with our Macedonian brothers — our shared history. Because we can't divide it. The pessimistic one is to continue in the same spirit and remain misunderstood by Europe and hated by Macedonians, our closest blood relations.

Just a quick riposte: I wouldn't say Macedonians are my "brothers." I have one biological sister, and the Macedonians are my neighbors and very nice people. I am against such metaphors as "brothers" and "blood relations" because they muddle bilateral ties.

Totomanova: A matter of metaphor (laughs).

Kyosev: As regards the pessimistic and optimistic scenario. The optimistic scenario is to talk to each other, and the pessimistic scenario is not to. The optimistic one also includes diplomatic gestures, cultural, social, economic communication. Then both languages will become closer, perhaps. And the pessimistic scenario includes senseless diplomatic and state acts that actually breed hatred.

Totomanova: Speaking of "brothers," all of us in the Balkans can claim a piece of a common cultural and historical heritage. This is our biggest problem. Everyone wants to be more deserving of piling up this cultural and historical baggage. And the "brothers" metaphor is a matter of taste…

Kyosev: However, this metaphor, Mr. Andreev, has some substance to it. I don't have brothers and sisters in Macedonia, but I do have 20 real relatives: first, second and third cousins. That is, real family ties connect me to Macedonia, although not to all Macedonians.

Totomanova: My family also hails from Pirin Macedonia, from Bansko.

Kyosev: So the metaphor is not so unfounded. Real family relationships do exist. What’s unfortunate is that historical destinies diverged. Political wills diverged. And now we have to fix that.

(This conversation, held on July 24, 2022, for Deutsche Welle in Bulgarian, was edited for clarity and length.)