VMRO’s struggle for autonomy and independence: Goce had doubts, Gjorche was opposed to Miss Stone’s kidnapping

- Post By Ad - MIA

- 15:18, 7 November, 2025

Skopje, 7 November 2025 (MIA)

Darko JANEVSKI

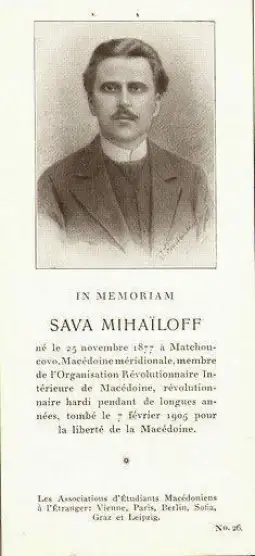

“Ever since Petrovden (St. Peter’s Day), we had been thinking about how to get money. We had a plan involving a Turkish bey in Dzhumaja, Suleyman Bey, but neither then nor during July were we able to capture him. When I crossed into Bulgaria on August 17, Chernopoev was already in Bansko, and the plan to kidnap Miss Stone was prepared. They were waiting for me to ask Delchev and Gjorche what they thought about it – whether to kidnap Miss Stone or not. Delchev and Gjorche didn’t believe we would get large sums for Miss Stone, and that’s why Gjorche didn’t agree to carry out the kidnapping, he was against it. I left on August 17 (1901) with Krsto Asenov and a few men, we went to Bansko and informed them that Delchev was hesitant,” recounted the Gevgelija vojvoda Sava Mihajlov in his memoirs about the preparations for one of VMRO’s most famous actions – the kidnapping of American missionary Ellen Stone and her companion Katerina Cilka.

In principle, Goce Delchev and Gjorche Petrov were not opposed to such actions, but based on Mihajlov’s testimony it can be concluded they had doubts about the success of the action and the amount of the ransom they could receive for such a person. The doubts in the group’s ability to carry out such an action stemmed from the organization’s previous, not very successful attempts to conduct kidnappings or blow up railways and bridges.

The Bey who stays at home

Indeed, the failed attempt to kidnap Suleyman Bey also testifies to this. Jane Sandanski described the event like this:

“I was heading to Dupnica, and together with Chernopeev we planned to capture a bey – Suleyman Bey, the son of the pasha from Dzhumaja. The two of us disguised ourselves and went to Dzhumaja to familiarize ourselves with the streets and the coffee houses where the bey would pass by or sit. We decided to kidnap him from a coffee house. But by chance, the bey didn’t leave his house for two days. We were with 20 men, four of whom were villagers armed with rifles. We even considered using bombs. We couldn’t keep the 20 men in the town for long, so we sent them back to the villages and remained with Chernopeev and Krsto Asenov…”

And so, the idea to kidnap the bey fell apart since he stayed home for two days. Fate wanted the kidnapping to be carried out, but the victim to be American. Gjorche denied being aware of this.

“The Miss Stone Affair had already happened. Her kidnapping happened without our knowledge. We knew that a plan was being prepared for another person,” Gjorche said. Then, some issues arose and Gjorche was sent to resolve them. “They did the deed, and then they didn’t know what to do after... We were preparing a plan to meet with them, with Sandanski, so I could give them instructions,” Gjorche recounted.

The kidnapping itself took place on a bend in the road no wider than three meters. On one side of the road rose steep cliffs, and on the other side was a ravine. The terrain itself explains why this location was chosen: once the convoy with Ellen Stone was stopped, there was simply nowhere to escape, and in the event of a shootout, the chances of any armed escorts of the convoy against the komitis were minimal.

“We waited all day and in the evening around 5 PM they came near. We were dressed in Turkish attire. We captured them,” Sandanski recounted.

According to Turkish documents of the event, published by Dragi Gjorgiev, most of the kidnappers wore fezzes, two had caps, and their heads were completely covered with bandanas.

“Three of them were dressed in Ottoman military uniforms, and although they all spoke Turkish, their manner of speaking revealed that they did not know the language well. Instructions were sent to the authorities in all local areas, as well as to all responsible officials, to capture the bandits – dead or alive,” stated the telegram sent on September 6, 1901, from the Salonica Vilayet and signed by Governor Tefik.

During the kidnapping, according to the report from the Ottoman Empire’s Minister of Foreign Affairs to the Grand Vizier dated September 15 of the same year, an Albanian man (Sandanski refers to him as a Turk) was killed after having the misfortune of passing through that part of the road at that very moment. He was an Albanian estate manager named Ibrahim bin Meshkar Ali from the village of Babjak, near Razlog, who, when the komiti tried to stop him, fired a shot and lightly wounded one of them. He was captured and immediately executed.

A hundred kilograms worth of money

“It was a perfect September day, the third of the month, clear, warm, and sunshiny, so that our spirits rose... There were just thirteen of us – unlucky number... We wound along the steep trail for some distance. Thus we approached a cliff known as the Balanced Rock, a bald crag of the mountain which here juts out into the valley, turning the stream to one side. At this point the pathway leads down into the water, so that travelers must ride into the swift current, pass around the rock, and strick the trail again on the father side. An admirable spot for an ambush. Suddenly we were startled by a shout: a command in Turkish, ‘Halt!’ I saw Mr. Usheva, who was then in the middle of the stream, start backward and attempt to turn her horse aside. An armed man had sprung toward her with uplifted musket-butt, as if to strike her from her saddle. She turned a horror-stricken face upon me, and then swayed as if to faint. Before any of us could say a word, armed men were swarming about us on all sides. They were crowded upon us, and fiercely demanded that we dismount,” Ellen Stone described the kidnapping after her return to the United States.

That is how the affair that caused significant international problems for the Ottoman Empire began. Today, in the United States, this incident is considered the country's first modern hostage crisis. From the outset, Turkish authorities believed Boris Sarafov was behind the kidnapping, although the blame was later shifted to Sandanski. In any case, it marked the beginning of a six-month epic, during which Miss Stone’s kidnapped companion, Katerina Cilka, would give birth to little Elena. The entire event concluded in February 1902 with remarkable success for the organization, which received 14.500 Turkish lira – or, as Sava Mihajlov testified, money weighing around 80 oka (approximately 96 kilograms).

The money was distributed among trusted people for safekeeping, and Goce Delchev personally made those decisions. Without his approval, no one was allowed to even consider allocating the funds in any way. According to Gjorche Petrov’s memoirs, the majority of that money was spent on the struggle against the Vrhovist wing of VMRO. A portion (around 200 lira) was also given to the Boatmen of Thessaloniki, and this was done by Delchev and Sarafov, in contrast to Ivan Garvanov (then president of the Organization’s Central Committee during the attacks) and Dame Gruev (who had his last meeting with Delchev shortly before the 1903 attacks regarding the Ilinden Uprising), both of whom were firmly opposed to the plan. Dame Gruev even believed that the Boatmen of Thessaloniki should be eliminated to prevent them from carrying out the idea, fearing that the attacks would provoke retaliatory actions that could jeopardize the entire organization.

According to some sources, the 14.500 lira received as ransom for Stone and Cilka were worth around US$72.500 at the time. Based on Ellen Stone’s letters to Protestant missions and preserved documents showing American efforts to raise funds for the ransom, the amount discussed was approximately US$100.000 at the time.

There are various methodologies for calculating the present-day value of historical U.S. dollars. According to the method yielding the lowest estimate, that sum today would be equivalent to nearly US$3.5 million if adjusted for inflation alone, and up to US$9.5 million when calculated by purchasing power. It was an enormous amount for that time, when the organization executed people for embezzling even just a few lira.

Gjorche Petrov on how the money was kept

“The money was brought by Sandanski, Krsto Asenov, and Sava Mihajlov – in gold, all in lira. They brought it to my room. I secretly returned from Trnovo for a few days. We divided it into small portions and gave them to various friends for temporary safekeeping. One part was left in Kostenec Banja, another in Vraca with relatives and acquaintances. People guarded the money like a holy relic, though there was fear behind it. They proved loyal. I gave the poet Strashimirov 3.000 lira to keep, Biolchev – 1.000, and a doctor who lived with relatives — 2.000 lira. Strashimirov’s wife Stefka guarded it like a relic – they handed it over. We didn’t even think to give them something as a token or reward. The money wasn’t taken all at once from those who kept it, but gradually, as it was spent. Delchev was called from the interior and a commission was formed: Delchev, N. Maleshevski, Tushe Deli Ivanov, and Stefanov, I think. They were tasked with deciding and overseeing the use of the money, specifically the portion designated for spending in Bulgaria. Another part was allocated for internal use and distributed across districts. Most of the money was spent here. None of the direct participants took any reward for themselves, and no changes in their lives full of hardship followed or were noticed. This money, in general, greatly helped strengthen the organization. The majority of it was spent here in the fight against members of the Vrhovist wing.”

This is noted in Gjorche's “Memoirs.” Note this part: “None of the direct participants took any reward for themselves, and no changes in their lives full of hardship followed or were noticed.” And this: “People guarded the money like a holy relic.” And finally, from Gjorche's “Memoirs” on this topic: “The majority of the money was spent here in the fight against members of the Vrhovist wing.”

Incidentally, Goce Delchev personally gave Jane Sandanski five lira to take to his father, who lived in extreme poverty, and Krste Asenov, through an intermediary, took money from his mother so he could buy civilian clothes and replace his komiti attire to descend from the mountains into Sofia.